Author: Kathryn Delaney CCA, CCH, CN

Investigating the ways that depression has been understood and managed throughout medical history is telling of its mysterious nature. In their paper investigating the historical understandings of depression as a disease, authors explore how it has been managed throughout history (Nemade). Once considered to be sourced from demonic influences, people who were “possessed” with the disease were often locked away. Popular Greek physicians such as Hippocrates, saw the conditions of the personality as an imbalance of the inner workings of the body, or the humors, while Romans, such as Cicero argued that depression was more an imbalance of the mind. During the mid-1600s, author Robert Burton published “The Anatomy of Melancholy”, which explored the psychological and social causes (such as poverty, fear and solitude) of depression. Burton’s encyclopedic work, recommended diet, exercise, distraction, travel, purgatives (cleansers that purge the body of toxins), bloodletting, herbal remedies, marriage, and even music therapy as treatments for the disease. However, the Age of Enlightenment followed shortly after and during this time depression was considered something that was inherited, and that it was an “unchangeable weakness of temperament,” as a result, many were put away in institutions. More recently, depression is said to be most successfully managed with therapy and/or medication. However new discoveries in the physiological connections between the Brain/Gut axis and the microbiome are beginning to shift how medical professionals consider treating the disease (Kelly et. al.) These new findings, along with studies on gut permeability, and studies on the gut microbiome and how it is influenced by stress, are building a path toward new frontiers of research that could revolutionize our understanding of depression as an illness and how to best manage the condition.

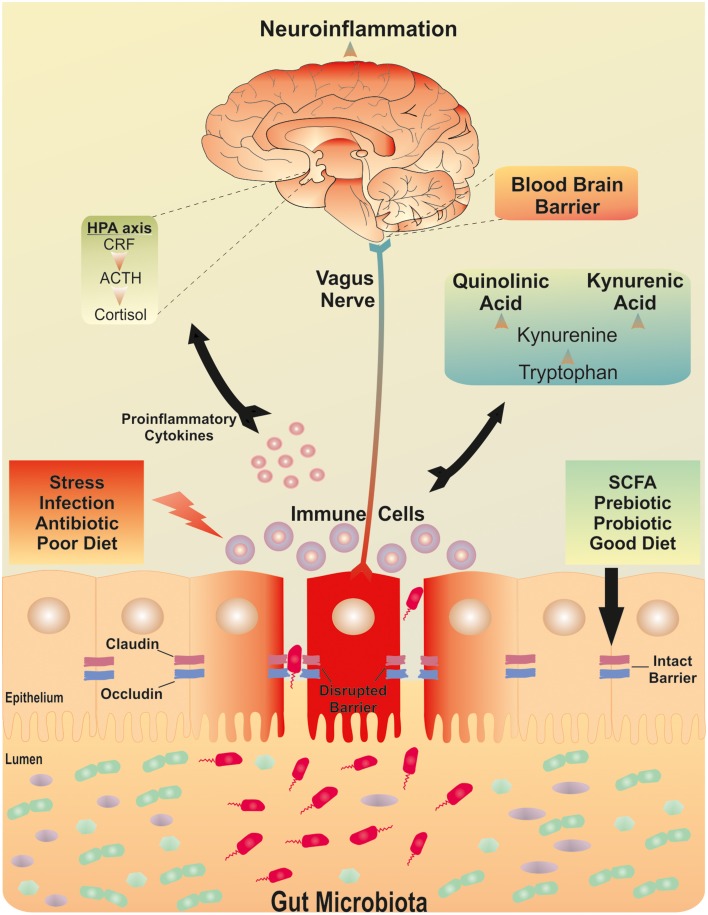

Emerging studies are connecting the links between gut microbiome and the central nervous system. Bidirectional signaling between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain has shown to be regulated at neural, hormonal, and immunological levels. This construct is known as the brain-gut axis and is vital for maintaining homeostasis within the body system. Bacterial colonization of the intestine has been shown to play a major role in the post-natal development and maturation of the immune and endocrine systems. This new wave of information implies not only a new understanding of stress-related conditions, dietary habits and psychiatric disorders, but also provides indications to possibilities in new treatments (Grenham). These innovative findings suggest that adjustments in gut microbiota may be able to modulate brain development, and the function and behavior by immune, endocrine and neural pathways of the brain-gut-microbiota axis (Kelly et, al.) Under these considerations, deficits in intestinal permeability are being considered to play a key role in chronic low-grade inflammation that is seen in disorders such as depression (Kelly et, al.) New studies are investigating the role that the gut microbiome plays in regulating intestinal permeability, and the consequences that occur within the central nervous system when it is disrupted.

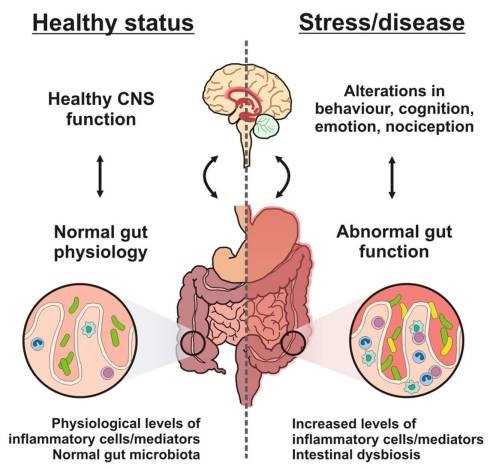

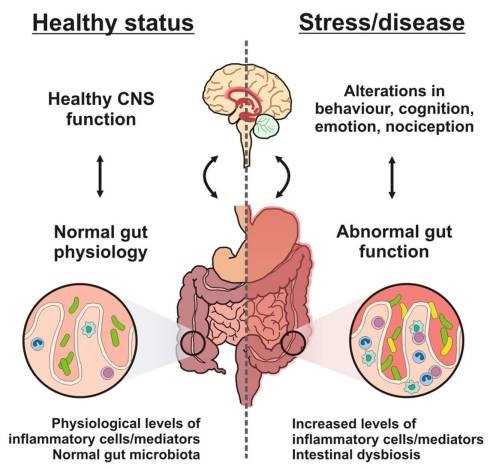

Brain–gut–microbe communication in health and disease. A stable gut microbiota is essential for normal gut physiology and contributes to appropriate signaling along the brain–gut axis and to the healthy status of the individual as shown on the left hand side of the diagram. Conversely, as shown on the right hand side of the diagram, intestinal dysbiosis can adversely influence gut physiology leading to inappropriate brain–gut axis signaling and associated consequences for CNS functions and disease states. Stress at the level of the CNS can also impact on gut function and lead to perturbations of the microbiota.

Brain–Gut–Microbe Communication in Health and Disease

Front Physiol. 2011;2:94.

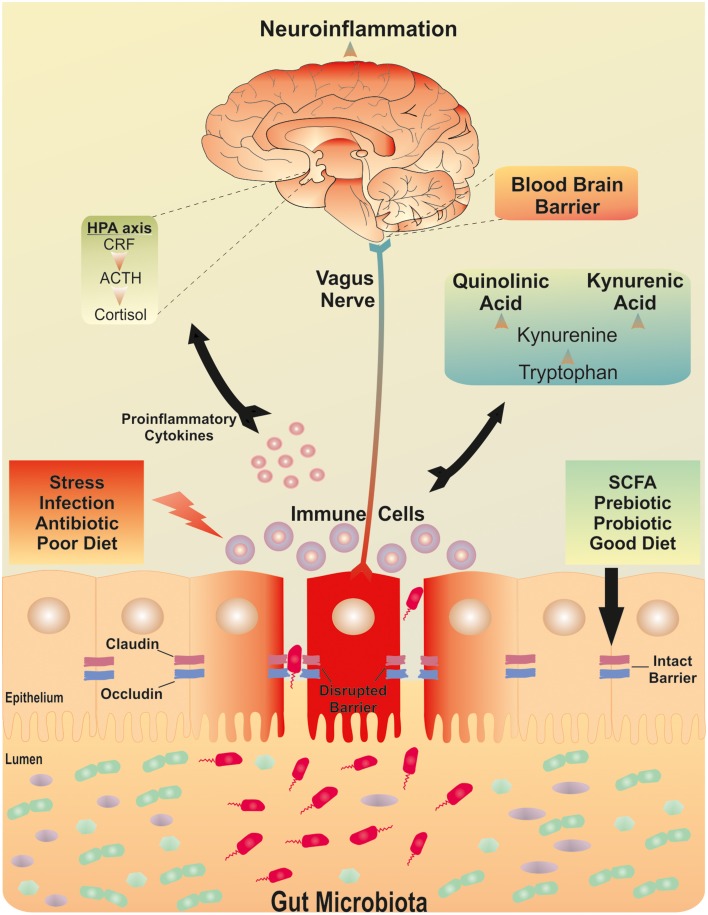

The function of the intestinal wall is maintained by tight junctions of protein structures that have transmembrane proteins that serve as a mechanical link between epithelial cells, and ultimately establish a barrier to paracellular diffusion of fluid and solutes (Kelly et al. and Ivanov et al.) The primary function of this barrier is to regulate the absorption of nutrients, electrolytes and water from the lumen into the circulation and to prevent the entry of pathogenic microorganisms and toxic substances from entering the bloodstream. For the most part, these functions are preserved by many of the natural features of the body including mucosal layer which secrets immunoglobulin and antimicrobial peptides which cover the epithelial cell lining. This works to facilitate gastro-intestinal transport, and is a protective layer against bacterial invasion. Alterations in gut microbiota have been associated with barrier dysfunction in both intestinal and extra-intestinal disorders (Greenwood and Vaarala et al.). In this way it has been observed that disruption of the gut microbiota may have implications for the sustenance of other key barrier functions within the body (Kelly et al). Recognition of structural similarities in the intestinal, placental and the blood brain barrier is beginning to open up new studies and connections in understanding of the phenomena now known as the gut-brain axis. Recent studies are strengthening the hypothesis that the blood brain barrier may also be vulnerable to changes in the gut microbiota (Kelly et. al).

A healthy adult human has around 100 trillion bacteria just in the gut, these bacteria are known as the microbiome. This is ten times as many bacterial cells as there are regular cells in the entire body. These bacteria are diverse in function, they express nearly 3 million genes, compared to the body’s estimate of 23,000, and have many useful digestive functions, including standing at the front line of defense from pathogenic microbes. Humans are both genetically and functionally dependent on these organisms for proper digestion, growth and development. It would seem of great importance that people ensure that they have healthy microbiomes in order to carry on the processes within the body that maintain life. This delicate system is what enables our bodies to absorb nutrients from the foods that we consume in order to run our entire body system. The bidirectional signaling system between the gut and the brain is regulated within the neural, endocrine and immune systems of the body (Grenham & Kelly et. al). These pathways are all under the influence of the gut microbiota, and together they comprise of the brain-gut-microbiota axis. One of the primary functions of the microbiota is the development and maintenance of the intestinal barrier within the lifespan of an individual (Kelly et. al). Some researchers consider it plausible that small alterations in microbiota early in life may predispose an individual to be vulnerable to neuro, endocrine, or immune, stress-related disorders in adulthood (Kelly et al.). This has been seen by further development of food allergies and mental illnesses later in life.

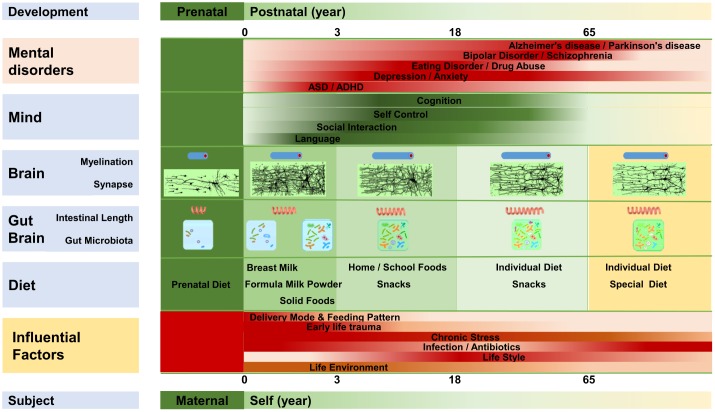

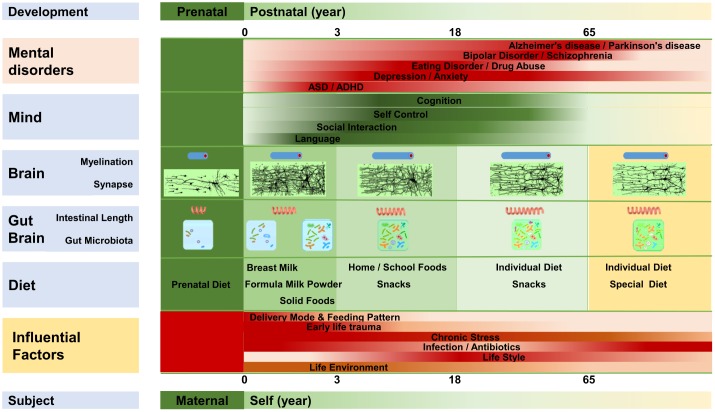

Due to findings illuminating the importance of the integrity of the intestinal barrier coupled with a healthy microbiome, it calls forth a need for further investigation as to what factors ultimately influence the structure and integrity of this inner boundary system and the microbiota itself. Research is revealing that the intestinal barrier is formed by the end of the first trimester of development (Kelly et al, and Montgomery et al.) “Epithelial cells with microvilli, goblet and enteroendocrine cells, appear by week eight of gestation and tight junctions are detected from week ten.” (Kelly et al and Louis and Lin). It has been shown that the functional development of the intestinal barrier continues to develop after the child has left the womb, and is influenced by both the method of birth (vaginal or caesarean), mode of feeding, and diet (Cummins and Thompson; Verhasselt). If the natural process of developing the microbiome is disrupted, which can often happen in the case of a premature birth, these children are often predisposed for immune disorders (Kelly). Infants born by caesarean section or receiving antibiotics have been shown to be at increased risk of developing metabolic, inflammatory and immunological diseases, potentially due to disruption of normal gut microbiota during a critical developmental time frame. Researchers have recently investigated whether probiotic supplementation can ameliorate the effects of antibiotics or caesarean birth on infant microbiota (Korpela). They found that the probiotic supplement had a strong overall impact on the microbiota composition, but the effect depended on whether the infant was at least breastfed. In the probiotic group, the effects of antibiotics and birth mode were either completely eliminated or reduced. The results indicate that it is possible to correct undesired changes in microbiota composition and function caused by antibiotic treatments or caesarean birth by supplementing infants with a probiotic mixture together with at least partial breastfeeding (Korpela). Aside from our birth experience and natal imprint, many other factors can alter and shape our initial microbiota as its nature is to shift with exposure to foods and people, including the consumption of common food allergens such as: wheat, corn, dairy, and soy. As individuals develop and engage with various circumstances in life the microbiota is further affected by environmental triggers such as vaccines, antibiotics, pharmaceuticals and pesticides (Greenwood). Scientists and researchers are beginning to link the exposure to these triggers to chronic conditions within the digestive system, as well as: asthma, diabetes, autism, and various autoimmune disorders (Greenwood). “According to gut-brain psychology, the gut microbiota is a crucial part of the gut-brain network, and it communicates with the brain via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. The gut microbiota almost develops synchronously with the gut-brain, brain, and mind. The gut microbiota influences various normal mental processes and mental phenomena, and is involved in the pathophysiology of numerous mental and neurological diseases.” (Liang) Overall there appears to be a negligence of western medicine and agricultural businesses to consider the effect of pharmaceuticals and chemicals on the digestive system and the implications to our overall health.

“The gut-brain, brain, and mentality develop almost synchronously throughout the lifespan. The gut-brain, brain, and mentality undergo similar developmental patterns; all three are susceptible to several factors that influence the gut microbiota. Myelination, intestinal length, and the gut microbiota develop almost synchronously. Diet plays an important role in the maturation of the gut-brain and brain, and mentality is regulated by the development of the brain and gut-brain. Microbiota disruption at different stages is likely to increase the incidence of different mental disorders.”

Liang. Gut-Brain Psychology: Rethinking Psychology From the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis

Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2018;12:33.

The inner lining of our intestines is made up of a series of tight junctions made of large protein complexes which regulate the passage of molecules through the epithelium. When everything is operating as it should, only selected molecules get through this lining and into the bloodstream to travel where they are needed in the body. The intestinal barrier is coated with a gastrointestinal mucosa which forms a protective lining within our small intestine which keeps the “not self” out, while allowing selected nutrients to pass into the blood stream. This GI mucosa can thin to the state of nonexistence, leaving the gut epithelium exposed. When the body experiences chronic stress or inflammation, the gut lining, which is made of tight junctions, loses its ability to act as a protective gateway for the bloodstream and instead becomes more of an open channel for larger amino acids, the passage of toxins, antigens, and bacteria to enter the bloodstream. This condition, now referred to as leaky gut syndrome, is the precursor for many auto-immune conditions and now, because of recent findings in the gut-brain axis, researchers are also finding connections to leaky gut and mental illnesses (Mu). Additionally, a damaged intestinal flora “dysbiosis”) has been shown to contribute to an increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa (“leaky gut”), which leads to an increased immune response and chronic neuroinflammation, showing to be a major cause of mental illness (Mörkl). Other causes of leaky gut syndrome include: prolonged use of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs – aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen and selective COX-2 inhibiters), corticosteroid drugs (Prednisone), Dysbiosis (and things that cause it, such as antibiotics), dysregulated or hyperactive immune response, hormonal imbalances, microbial infections, food intolerances, chronic stress/chronic sleep debt, excessive/prolonged use of alcohol, tobacco, coffee, glycated compounds in processed foods, anything that releases free radicals in the gut, and even excessive exercise (Bergner et, al; Lamprecht).

“The brain-gut-microbiota axis. Postulated signaling pathways between the gut microbiota, the intestinal barrier and the brain. A dysfunctional intestinal barrier or “leaky gut” could permit a microbiota-driven proinflammatory state with implications for neuroinflammation.”

Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders

Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2015;9:392.

Combined along-side this understanding we have the compounding effect of modern lifestyles that keep people inside, which often leaves individuals deficient in vitamin D, a necessary component to create tight junctions in the epithelial lining of our gut. While there has been an understanding for some time that seasonal depression can be related to lack of time exposed to the sun, and ultimately vitamin D deficiency, this understanding also stirs reflection that this seasonal condition could also be related to the deficiency of vitamin D affecting the tissue of the stomach lining. When the body is deficient in vitamin D it could ultimately affect the junctions within the epithelial lining of the gut, which has implications along the gut-brain axis, and subsequently mental mood, and depressive states.

In the Westernized world today, depression and anxiety are the most frequently diagnosed disorders (CDCP). Over time, the number and frequency of diagnoses have indeed grown due in part to greater awareness of manifestations of disease symptoms, but also due to the pace of modern life, change in diet, and increases in daily stress (Schnorr). Data suggests that psychiatric disorders are expected to dramatically increase in the years to come (Baxter). Despite intensive efforts to improve mental health treatment, only one third of patients with depression reach complete remission with psychopharmacological therapy (Morkl). In cases of severe depression, combination therapies of antidepressants and psychotherapy are usually recommended, however many of the prescribed drugs cause unwanted side effects, leading approximately 50% of psychiatric patients to prematurely discontinue their psychopharmacological treatment (Mörkl).

Although extensive studies have been conducted within the realm of psychopharmacological treatment, the progress in developing effective therapies for these diseases has been slow, begging for the need to look toward new alternatives (Liang). In recent years we began seeing a rapid increase in the number of studies investigating the connection between the quality of our diet and mental health. For example, studies revealed that a high-quality diet was connected to lower rates of depression and lower suicidal risk (Lai).

The exact mechanisms of how diet affects mental health are currently widely being explored. There are increasing numbers of studies which support the evidence of inflammation in the pathophysiology of mental health disorders, including depression, and how eating habits influence this (Tolkien).

Our brain relies on a continuous energy supply sourced from the nutrition obtained in our diet, including: amino acids, lipids, vitamins, minerals and trace elements. A traditional diet with whole foods including vegetables, fruit, seafood, fish, wholegrains, lean meat and nuts is a good prevention of a number of diseases (Guasch-Ferré). Our dietary habits modulate gut bacteria, the immune system and circuits of inflammation which are known to be involved in the development of psychiatric disorders such as depression. In his paper discussing the benefits of an anti-inflammatory diet for depression disorders, Tolkein states, “There is a large body of evidence which supports the role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of mental health disorders, including depression. Dietary patterns have been shown to modulate the inflammatory state, thus highlighting their potential as a therapeutic tool in disorders with an inflammatory basis.” The author continues, highlighting the potential of food as a therapeutic tool in disorders that are of inflammatory basis. One diet that has been studied and seen to be of benefit for improving recurrences of depression is the Mediterranean-style diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, olive oil, fish and whole grains (Roca et. al and Garcia-Mantrana). This diet is different than the Standard American Diet, or SAD diet, which focuses on red meat, processed foods, high-fat dairy, refined grains, sugary foods, and sodas, with minimal consumption of fresh fruit, vegetables, fish, whole grains and legumes. The SAD diet has been shown to cause chronic sub-acute inflammation within the body (Koopman). Over the past decade, research has shown that diet and gut health affects symptoms expressed in stress related disorders, depression, and anxiety through changes in the gut microbiota (Schnorr). In this reflection, correcting leaky gut, adjusting to more anti-inflammatory dietary foods, and taking beneficial supplements, are beginning to be considered as possible therapeutics for depression and other mental illnesses (Haroon).

Aside from anti-inflammatory diet, there are several supplements that are being looked at for their benefits in bringing balance to the microbiome and repairing intestinal barrier function. A successful protocol would need to be holistic in nature and all-encompassing of the many influences that affect the condition. This commands for a multi-directional approach including: dietary support and education, nutrient supplementation, food allergen removal, and change of lifestyle incorporating more exercise, time spent outdoors and time shared with community. In order to best support individuals with diagnosed anxiety, depression and other mental illnesses (in addition to a range of others) the first step on a path to balance starts with integrative wellness. Recent studies are pointing in the direction of starting with digestive health, and becoming nutritionally replete. “Various microbiota-improving methods including fecal microbiota transplantation (which can be useful, although it is not a first line of action), probiotics, prebiotics, a healthy diet, and healthy lifestyle have shown the capability to promote the function of the gut-brain, microbiota-gut-brain axis, and brain” (Liang). Due to the relationship of the gut-brain axis, it is not a surprise to see that many of the same supplements have shown to be of benefit to improving imbalanced mental associated conditions such as depression and anxiety. These supplements and their associated benefits, follow:

Probiotics – Taking probiotics by means of ingestion has shown to rebalance microbiota in infants that were born caesarean or whom had to take antibiotics and it improved their overall health (Slyepchenko). Two specific strains that have been studied for their ability to repair the structural integrity of the intestinal lining are Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces boulardii and (Ahrne and Terciolo). Several recent reports have shown that probiotics can reverse the effects of leaky gut syndrome by enhancing the production of tight junction proteins (Mu). In adults, taking probiotics has shown to improve mental well- being and in recent scientific studies probiotics have shown to improve the mental states of diagnosed schizophrenics (Okubo). While taking probiotics has revealed themselves to be of pronounced value, it is important to note that there may be some health scenarios where probiotics should be used with caution (Kothari). Some researchers suggest that some clinical conditions including malignancies, leaky gut, diabetes mellitus, and post-organ transplant convalescence would likely fail to reap the benefits of probiotics because it could leave the system susceptible to bacteria going to parts of the body where they could cause damage. This possibly calls for an attention to protocol in a strategic series of application.

Prebiotics – These are the indigestible dietary fibers we get from food that probiotics use to flourish and grow. Whereas probiotics are living organisms, prebiotics are not. Prebiotics can help the bacteria that is naturally found in your intestines to flourish. Prebiotics benefit the individual microbiome in that it feeds it and supports, and in this way it benefits the overall structure of the intestinal barrier (Liu and Liang).

Vitamin D – This vitamin is actually a hormone that we create within the subcutaneous fat layers within our skin when our skin is exposed to sunlight at specific times of the year. Vitamin D is required to build the tight junctions necessary for the intestinal lining to remain healthy. With an expanding, or more commonly adopted lifestyle pattern to work indoors and therefore have less time exposed to the sun, westernized countries are showing an increase in deficiencies of vitamin D.

Omega–3 fatty acids – Not only does our brain thrive on healthy fats, we need a balance of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in order to have a healthy inflammatory response. Omega-3 fatty acids also have the following main mechanisms of action: they modulate neurotransmitters through reuptake inhibition, synthesis and receptor binding, support neurogenesis by enhancing BDNF and also have anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects (Mischoulon).

Researchers state that through observational understanding and meta-analytic studies the additional supplements of magnesium, 5 HTP, Selenium, Lycopene, folic acid, selenium and calcium may also have an impact on reducing depression. In a separate study, supplementation of vitamin B6 in women, and higher intake of B12 in men, was seen to have reduced major depressive disorder, according to Roca, et. al. In the same study, depression was significantly associated with low selenium blood levels and low levels of dietary selenium were also associated with an increased risk for major depressive disorder. The research also showed low dietary calcium to be associated with self-rated depression in middle-aged women. Additionally, the consumption of processed foods such as fried foods, refined grains, and refined sugars were associated with the conditions of depression and obesity, while eating a more traditional Mediterranean-style diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, olive oil, fish and whole grains was associated with reduced depression. Similar findings were observed in populations of people with diabetes, and older people.

Studies are revealing that food and lifestyle changes are demonstrating greater efficacy for states of mental illness and to prevent other progressive diseases, than pharmaceutical medications. This commands for a new consideration in methods and a change of strategy to support these conditions. Rather than considering conditions of mental illness to be an imbalance of chemistry that can be modulated with pharmaceutical prescriptions, researchers are pointing the way to an integrative approach to well-being through food and the digestive microbiome. While currently westernized medical doctors are area-specific, and caretakers are specialized in one area or system of the body, recent findings in regard to the benefits of dietary changes and supplementation command for a new, more simplified systemic approach to wellness.

There is a growing body of evidence which explores the role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of mental health disorders, including depression. Research continues to reveal that changes in dietary patterns modulate the inflammatory state, which highlights their potential as a therapeutic tool in disorders with an inflammatory basis (Tolkien). Mental disorders and neurological diseases are becoming a rapidly increasing medical burden and growing concern for our society. Although numerous studies have been conducted regarding the benefits of dietary changes and advances in understanding in regard to the role of the microbiota in our overall mental health, the progress in developing effective therapies for mental disorders has still been slow (Liang). The most practical approach to mental health disorders which is also the most effective and affordable, appears to be a change in diet, supplemental support and education. Despite these new understandings, there are several limitations in regard to initiating these changes in an individual’s daily life.

In looking at the disease of mental illness from afar and considering these new therapeutic approaches, it is the way that the illness has been classified in the recent past that will in many ways be one of the biggest hurdles to overcome. The stigma of mental illness continues to anchor in a realm of chemical imbalances within the mind, rather than understood as an imbalance anchored in the digestive system. The western medical approach has most often strategized their medications to either shut down specific receptors in the brain or excite others, inherently trying to control the inner workings of the human body. Despite their numerous attempts to arm-wrestle mental illness with an assortment of perceived levers that just needed tweaks and adjustments, this approach has not been effective. The root of mental illness has revealed itself to be a bit deeper within a more intelligent integrated system. Research has revealed that the only practical and effective way to treat mental illness is to consider the origin of the illness itself, problems within the digestive system and disruptions in the human microbiome. As seen in recent studies, a protocol built around a foundation of nutrition serves as the most practical therapeutic for the conditions of mental illness, depression and anxiety. With this new understanding of the gut-brain axis, the role of the microbiome, and the compounding knowledge in regard to the long-term effects of leaky gut syndrome, a holistic protocol needs to be considered that is built around education and compassion.

Nutritionists that focus on food as medicine are trained to offer new strategies within the realm of integrative wellness by providing support and education that can ultimately help lay a new foundation where vitality can flourish. The pace of modern life has habituated people to reach toward not only quick fixes by way of medication, but also convenient foods that are affordable. Many of the foods which are readily available for consumption are foods that are common to the S.A.D. diet, which increase inflammation in the body, such as fried foods, refined grains, and refined sugars. What compounds this, is that many people consume foods that they are intolerant to and in recent generations many people were raised in single family homes and were not raised with the knowledge or skills in food preparation, which leads to them having difficulty transitioning to new foods. In addition, due to the pace of western lifestyle, people have a shortage of time to prepare food. Ultimately, there appears to be an underlying chronic stress picture interwoven into the threads of our landscape which would be useful to take a look at as well. This also points to the support of nutrition and lifestyle as the ultimate key to supporting mental and physical wellness.

These new findings regarding the gut-brain axis and how inflammatory diet can actually be the root of imbalance in the overall system, calls for a new outline to be drawn around mental health, depression and anxiety conditions that involves more holistic view of the body than just chemistry alone. The research findings discussed above call for a new attention and strategy in the realm of mental illness and overall wellness, which are showing to be connected to the state of digestive health and the quality of the microbiome. A new approach to therapeutics is on the horizon. Our current society has been educated to believe that mental illnesses can be remedied with pharmaceuticals that will “correct” an imbalance within their brain, or through talk therapy to uncover and salve old emotional wounds, recent research are showing these to be minimally effective. When one considers that food choices and stress are some of the most basic and compounding sources of inflammation in the body, and that this ultimately causes inflammation within the brain, this begs for a more holistic, integrative approach to therapeutics that is centered in, or focused on digestion. Recently published intervention trials provide preliminary clinical evidence that dietary interventions in clinically diagnosed populations are feasible and can provide significant clinical benefit to patients with diagnosed mental illnesses (Marx). We are in the midst of restructuring our sense of understanding in the realm of mental health; this reveals the need for health care providers to focus on integrative approaches that rely on nutrition as a pivotal piece of health care.

Currently, the western model is allopathic in approach. In recent decades, medical providers trained in traditional western medicine have had a leniency toward treating any and all symptoms found within the body with the use of pharmaceuticals and over-the-counter medication. Rather than look toward correcting imbalances within the body by suggesting the removal of offending foods and substances, medications are suggested that are centered on quieting the disruption, which inevitably results in exacerbating the condition, resulting in more chronic ailments. The new research calls for the need for health professionals to encourage their patients to start approaching their health differently and for health care providers to support their patients in doing this. To give a simple example, a person may be in the habit of taking an antacid when they experience acid reflux on a daily basis. In taking a sober look at the signaling system of the body, an alternative, and I would argue logical approach would be the avoidance of the offending food which causes the acid reflux, rather than continuing to eat the offending food out of habit or convenience, and taking an antacid regularly. By taking the antacid, the person may experience relief from the symptom, but the cause of their symptom hasn’t been considered. For instance, the most common triggers for acid reflux, or GERD, are food allergies such as dairy, which increases stomach acid, alcohol, antihistamines, pain medications, asthma medications, calcium channel blockers, citrus fruits, fatty foods made with trans fatty acids, spicy foods, coffee, smoking, and sometimes even peppermint. If one wants to remove the root of an illness, it does not serve them to just trim the growing leaves regularly, or cover them with a blanket. Any gardener can share this concept, they have to take on the task of removing the weeds from their garden that strangle out the other plants that they want to grow. Similarly, the digestive system could be seen as where we till our own health. By consuming foods that we are sensitive to, it is in a way, throwing seeds of weeds into our own garden, we allow health situations to grow into conditions that strangle out our vitality.

When we consider the research discussed above, the amount of inflammation that is caused by eating certain foods and taking medications, how this effects our microbiome, how this goes on to effect digestive health, the gut-brain axis, and the ultimate manifestations that are revealed in mental and physical imbalances, we can begin to understand why trimming the leaves of manifestation with pharmaceutical chemistry, will never be able to bring balance or health to the body. There are now consistent mechanistic, observational and interventional data to suggest diet quality may be a modifiable risk factor for mental illness” (Marx). Ultimately, research is showing that mental imbalances, and states of anxiety and depression, along with a number of other health conditions, are best served with a new approach, by tending to the root of wellness with proper food choices and supplementation. Due to the heavy reliance on pharmaceuticals to remedy most health conditions, and how these substances further effect the gut microbiome and the permeability of the gastrointestinal tract, we can begin to see how the long-term effects have been affecting our state of health as a society, by the increase in mental illnesses, depression, auto-immune conditions, etc. This major imbalance of understanding and leniency toward medication, could be considered a large component of why health conditions are on the rise in the U.S. and other westernized nations.

In many ways the veil that pharmaceuticals cloaks over chronic conditions is thinning, and a new landscape is being viewed for the first time. These limitations reveal a need to shift our focus away from treating illnesses of the mind and body with pharmaceutical medications and instead, to shift our attention and efforts toward the resurgence of the concept of food as medicine. Instead of a singular, one direction approach of closing off receptors or exciting others with complicated chemistry, which is the typical strategy of medications, these new findings reveal a three-dimensional picture of interactive systems that beg to be approached in a holistic manner. Some researchers are seeing new possibilities available in a growing field of Nutritional Psychiatry and suggest that this evidence calls for supporting policy change that improves the food environment at the population level (Jacka). It appeals for consideration of the western healthcare system to begin to incorporate nutritionists for integrative support and education to build a bridge into the horizon toward a sensible healthcare system that encompasses these new understandings. The most successful approach will consider the individual before the illness itself. Rather than seeing the mental illness as a chemical imbalance to be remedied with pharmaceutical drugs, scientists are beginning to connect the dots between a realm of subtle (or not so subtle) malnutrition, mental illness and chronic disease. Thankfully, we have moved away from the times of using purgatives and bloodletting as remedy’s for depression and mental illness. However, in order to bring balance to the condition long term, it is necessary to consider the interplay between the gut-brain axis, the microbiome, and the dietary habits of an individual. By embracing this knowledge, there is a possibility to see a great shift toward holistic health in our population.

Bibliography

Ahrne S1, Hagslatt ML. Effect of lactobacilli on paracellular permeability in the gut. Nutrients. 2011 Jan;3(1):104-17. doi: 10.3390/nu3010104. Epub 2011 Jan 12.

Bergner, P. Advanced Herbalism Notes: Digestive System Pathology & Therapeutics (class notes). 2018

Baxter AJ, Patton G, Scott KM, Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA: Global epidemiology of mental disorders: what are we missing? PLoS One 2013; 8:e65514.

Dean AL, Armstrong J. “Genetically Modified Foods.” American Academy of Environmental Medicine (AAEM). Community Resource AAEM Position Paper, May 2009. Online document at: http://www.aaemonline.org/gmo.php Accessed August15, 2015

Dean AL, Rea WJ, Smith CW, Barrier AL. “Electromagnetic and Radiofrequency Fields: Effect on Human Health.” American Academy of Environmental Medicine (AAEM). Community Resource AAEM Position Paper, April 2012. Online document at: http://www.aaemonline.org/emf_rf_position.php Accessed August15, 2015

Garcia-Mantrana I1, Selma-Royo M1, Alcantara C1, Collado MC1. Shifts on Gut Microbiota Associated to Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Specific Dietary Intakes on General Adult Population. Front Microbiol. 2018 May 7;9:890. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00890. eCollection 2018.

Greenwood, Michael., MB, BChir, FCFP, CAFCI, FAAMA. “Dysbiosis, Spleen Qi, Phlegm, and Complex Difficulties.” Medical Acupuncture. Jun 1, 2017; 29(3): 128–137.

Grenham S. Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Frontiers in Physiology. 2011 Dec 7;2:94. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094. Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. eCollection 2011.

Guasch-Ferré M, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Estruch R, Corella D, Fitó M, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Fiol M: The PREDIMED trial, Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: how strong is the evidence? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2017; 27: 624–632.

Haroon E1, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012 Jan;37(1):137-62. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.205. Epub 2011 Sep 14.

Jacka FN. Nutritional Psychiatry: Where to Next? EBioMedicine. 2017 Mar;17:24-29. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.020. Epub 2017 Feb 21.

Kelly, John R., Kennedy, Paul, Cryan, John F., Dinana, Timothy G., Clarke, Gerard and Hyland, Niall P. “Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, Oct. 14, 2015.

Koopman M1, El Aidy S; MIDtrauma consortium. Depressed gut? The microbiota-diet-inflammation trialogue in depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017 Sep;30(5):369-377. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000350.

Korpela K1,2, Salonen A3, Vepsäläinen O4, Suomalainen M4, Kolmeder C5, Varjosalo M6, Miettinen S6, Kukkonen K7, Savilahti E8, Kuitunen M8, de Vos WM3,9. Probiotic supplementation restores normal microbiota composition and function in antibiotic-treated and in caesarean-born infants. Microbiome. 2018 Oct 16;6(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0567-4.

Kothari D. Probiotic supplements might not be universally-effective and safe: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. Patel S, Kim SK. 2019 Mar;111:537-547. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.104. Epub 2018 Dec 28.

Lai JS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Clinical Nutrition 2013; 99. Hiles S, Bisquera A, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Attia J.181–197.

Lamprecht M. Exercise, intestinal barrier dysfunction and probiotic supplementation. Med Sport Sci. 2012;59:47-56. doi: 10.1159/000342169. Epub 2012 Oct 15.

Liang S. Gut-Brain Psychology: Rethinking Psychology From the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Frontiers in Integrative Neurosciences. 2018 Sep 11;12:33. , Wu X, Jin F. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2018.00033. eCollection 2018.

Liu X. Modulation of Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis by Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Diet. J Agric Food Chem. 2015 Sep 16;63(36):7885-95. Cao S2,3, Zhang X. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02404. Epub 2015 Sep 1.

Marx W. Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2017 Nov;76(4):427-436. , Moseley G2, Berk M2, Jacka F. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117002026. Epub 2017 Sep 25.

Mischoulon D, Freeman MP: Omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry. Psychiatry Clinical Studies 2013; 36: 15–23.

Mörkl, Sabrina. The Role of Nutrition and the Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatry: A Review of the Literature. Neuropsychobiology. Jolana Wagner-Skacel, Theresa Lahousen, Sonja Lackner, Sandra Johanna Holasek, Susanne Astrid Bengesser, Annamaria Painold, Anna Katharina Holl, Eva Reininghaus. DOI: 10.1159/000492834. September, 2018.

Mu Q1. Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. Kirby J1, Reilly CM2, Luo XM1.doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598. eCollection 2017; 2017 May 23;8:598

Nemade, Rashmi Ph.D, et.al. “Historical Understandings Of Depression.” MentalHelp.net, https://www.mentalhe lp.net/articles/historical-understandings-of-depression.*

Okubo R. Effect of bifidobacterium breve A-1 on anxiety and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019 Feb 15;245:377-385. , Koga M, Katsumata N, Odamaki T, Matsuyama S, Oka M, Narita H, Hashimoto N, Kusumi I, Xiao J, Matsuoka YJ. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.011. Epub 2018 Nov 5.

Pratt, Ph.D. “Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Laura A. and Brody, Debra J. M.P.H.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.htm.*

Roca, Miquel. Prevention of depression through nutritional strategies in high-risk persons: rationale and design of the MooDFOOD BMC Psychiatry. Elisabeth Kohls, Margalida Gili, Ed Watkins, Matthew Owens, Ulrich Hegerl, Gerard van Grootheest, Mariska Bot, Mieke Cabout, Ingeborg A. Brouwer, Marjolein Visser, Brenda W. Penninx, and on behalf of the MooDFOOD Prevention Trial Investigators. . 2016; 16: 192. Published online 2016 Jun 8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0900-z

Schnorr, Stephanie L. Integrative Therapies in Anxiety Treatment with Special Emphasis on the Gut Microbiome. Harriet A. Bachner. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 89(2016) p 397-422.

Slyepchenko A. Gut emotions – mechanisms of action of probiotics as novel therapeutic targets for depression and anxiety disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(10):1770-86. , Carvalho A, Cha D, Kasper S, McIntyre, R.

Swanson NL. Genetically Engineered Crops, Glyphosate and the Deterioration of Health in the United States of America. J Organic Syst. 2014;9(2):6–37. Leu A, Abrahamson J, Wallet B. Online document at: http://www.organic-systems.org/journal/92/JOS_Volume-9_Number-2_Nov_2014-Swanson-et-al.pdf Accessed August 15, 2015.

Tolkien, K. An anti-inflammatory diet as a potential intervention for depressive disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition. 2018 Nov 20. pii: S0261-5614(18)32540-8. Bradburn S, Murgatroyd C. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Burden of Mental Illness. Mental health. 2013.